Wow! Suddenly a whole month has passed since my last post. How time flies once the college semester begins. I think I'm going to need to develop a reminder system so such a delay doesn't reoccur...

This fall has been remarkable for the number of clear nights - except on nights when celestial events are happening, of course. The Draconid meteor shower peaked over the weekend and according to those who observed it there was a fairly significant outburst during the peak, up to a rate of hundreds per hour. Here in Oneonta, it was cloudy. There was also a solar flare that produced northern lights visible as far south as Kansas, but here in Oneonta it was cloudy. Such is life. There is a prediction for moderate aurora activity on Oct. 14-15, when a coronal hole on the Sun rotates Earthward. Keep your eyes peeled!

So what's coming up that is worth checking out? Another meteor shower! The Orionid meteor shower peaks during the night of October 20/21. Like the Eta Aquariid meteor shower earlier this spring, the Orionis meteor shower also results from debris left behind by Halley's Comet. Its name comes from the fact that its radiant, the point from which the meteors appear to originate, lies in the constellation Orion.

The view looking east as Orion rises on the night of Oct. 20/21, seen at 11:30 p.m. EDT.

This meteor shower typically produces around 20 meteors per hour, though it can peak at 60 per hour on good years. During the few days leading up to the 20th and the few days afterward, occasional meteors can be seen as activity rises up to the peak and drops off afterward. Although the radiant is located in Orion, it's actually better to look roughly 90 degrees away from the radiant. This provides the best opportunity to see those meteors that give us a glancing blow, rather than the ones that travel more-or-less right at the viewer. I recommend facing east and looking up. It'll be cold out there, so bundle up! And while you're looking, check out Jupiter.

As a foreshadowing of things to come, next year looks great for comet viewing. Two new comets have recently been discovered that could shine bright enough to be seen with the naked eye! C/2012 S1 (ISON) and C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) will be two comets to keep up with as they rapidly close their distance between themselves and the Sun. It is thought that neither comet has made an approach to the Sun before, meaning there could be a lot of frozen ice and gas present to put on a show as it sublimates into space.

Happy viewing!

A guide to keep you informed about the night sky over Oneonta, NY, brought to you by the astronomer at the SUNY College at Oneonta.

Thursday, October 11, 2012

Friday, September 14, 2012

Where are all the planets?

The last few nights here in Oneonta have been just spectacular! No wind, no clouds, no haze, steady seeing, and reasonable temperatures. The astronomer can't ask for circumstances better than these. If you stepped outside during the evening, however, you may have asked yourself one question.

Where did all the planets go?

We've been treated to a plethora of planets this summer: Jupiter and Venus were around during the early summer until our sister planet's transit in early June. Then Saturn and Mars were the stars of the show during their conjunction in the late portion of the summer. However, they too have now drifted down into the glow of the sunset as the ecliptic (the path the Sun traces out through the sky and the path that the planets closely follow) dips low at a shallow angle in the southern sky...and we are left with nothing for the time being.

So when will the planets return? Unfortunately, the remainder of September offers us nothing but an opportunity to exercise patience as October approaches. For those who don't mind staying up past midnight, Jupiter rises in the east with Taurus and Orion, and Venus rises shortly before the Sun, but for those of you who cherish your hours of sleep, there are no opportunities for several weeks yet.

What, then, is a person supposed to view at night if the planets are nowhere to be seen and the Moon is in its New Phase (which occurs in a couple days)? This might be an excellent time to re-familiarize yourself with the constellations of the early autumn sky. Ursa Major dips low in the north right now, so you may need to use Cassiopeia to locate the North Star.

High above your head lies the three bright stars that form the asterism called the Summer Triangle. Named Vega, Deneb, and Altair, these stars form an isosceles triangle that points generally in a southern direction for most of the night, with Altair at the southern tip. However, it is a constellation adjacent (in the east) to the Summer Triangle that leads us to our object of interest. Rising in the east before sunset is the "Great Square" of Pegasus, the flying horse. Flying upside-down, this horse rises head and front legs first, with its square body coming next. Along the northeastern horizon, two trails of stars that look like its rear legs rise with it.

However, these rear legs actually comprise the constellation of Andromeda. These two trails of stars represent the princess rescued by Perseus from the jaws of the great sea monster Cetus. Within this constellation lies the Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

This galaxy is one of our Milky Way Galaxy's closest neighbors, lying a scant 2.5 million light-years away. Resembling the Milky Way in both its spiral shape and size, the Andromeda Galaxy is currently hurtling toward the Milky Way at breakneck speed, destined for collision some 5 billion years from now. This NASA website about the upcoming collision contains some nice images and video simulating the night sky as the intersection approaches. While it is described as a collision, the large distances between stars in both galaxies mean that they will more-or-less pass through each other at first, with few to none actual stellar collisions. Gravity's ceaseless pull will then cause them to double back on each other and ultimately merge together to form a large elliptical galaxy. Gas clouds will light up with star formation. If anyone is alive to witness the event, it should be spectacular - though there is a nonzero chance of that witness' home planet being flung out of the galaxy altogether or traded from one to the other during the first couple passes through. How cool would it be to live in the Milky Way Galaxy at first and then get traded to the Andromeda Galaxy as they interact with each other?!

If you have binoculars or a telescope, turn them to the Andromeda Galaxy and ponder this future. Practice star-hopping from Beta Andromedae to Mu Andromedae to Nu Andromedae and ultimately to M31. Getting to know where these objects are is half the fun!

Happy viewing!

Where did all the planets go?

We've been treated to a plethora of planets this summer: Jupiter and Venus were around during the early summer until our sister planet's transit in early June. Then Saturn and Mars were the stars of the show during their conjunction in the late portion of the summer. However, they too have now drifted down into the glow of the sunset as the ecliptic (the path the Sun traces out through the sky and the path that the planets closely follow) dips low at a shallow angle in the southern sky...and we are left with nothing for the time being.

So when will the planets return? Unfortunately, the remainder of September offers us nothing but an opportunity to exercise patience as October approaches. For those who don't mind staying up past midnight, Jupiter rises in the east with Taurus and Orion, and Venus rises shortly before the Sun, but for those of you who cherish your hours of sleep, there are no opportunities for several weeks yet.

What, then, is a person supposed to view at night if the planets are nowhere to be seen and the Moon is in its New Phase (which occurs in a couple days)? This might be an excellent time to re-familiarize yourself with the constellations of the early autumn sky. Ursa Major dips low in the north right now, so you may need to use Cassiopeia to locate the North Star.

High above your head lies the three bright stars that form the asterism called the Summer Triangle. Named Vega, Deneb, and Altair, these stars form an isosceles triangle that points generally in a southern direction for most of the night, with Altair at the southern tip. However, it is a constellation adjacent (in the east) to the Summer Triangle that leads us to our object of interest. Rising in the east before sunset is the "Great Square" of Pegasus, the flying horse. Flying upside-down, this horse rises head and front legs first, with its square body coming next. Along the northeastern horizon, two trails of stars that look like its rear legs rise with it.

However, these rear legs actually comprise the constellation of Andromeda. These two trails of stars represent the princess rescued by Perseus from the jaws of the great sea monster Cetus. Within this constellation lies the Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

This galaxy is one of our Milky Way Galaxy's closest neighbors, lying a scant 2.5 million light-years away. Resembling the Milky Way in both its spiral shape and size, the Andromeda Galaxy is currently hurtling toward the Milky Way at breakneck speed, destined for collision some 5 billion years from now. This NASA website about the upcoming collision contains some nice images and video simulating the night sky as the intersection approaches. While it is described as a collision, the large distances between stars in both galaxies mean that they will more-or-less pass through each other at first, with few to none actual stellar collisions. Gravity's ceaseless pull will then cause them to double back on each other and ultimately merge together to form a large elliptical galaxy. Gas clouds will light up with star formation. If anyone is alive to witness the event, it should be spectacular - though there is a nonzero chance of that witness' home planet being flung out of the galaxy altogether or traded from one to the other during the first couple passes through. How cool would it be to live in the Milky Way Galaxy at first and then get traded to the Andromeda Galaxy as they interact with each other?!

If you have binoculars or a telescope, turn them to the Andromeda Galaxy and ponder this future. Practice star-hopping from Beta Andromedae to Mu Andromedae to Nu Andromedae and ultimately to M31. Getting to know where these objects are is half the fun!

Happy viewing!

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

The SUNY Oneonta 1-meter Telescope

With the Clear Sky Chart indicating two clear nights in a row, I decided to get out the 1-meter telescope owned by SUNY Oneonta to do some observing tests before tonight's public viewing. As evening approached, I was joined by some local wildlife:

The 1-meter telescope is mounted on a trailer, which makes for convenient travel if one wanted to take it to an event.

This telescope is designed with three mirrors: a primary mirror 1 meter in diameter, a secondary mirror up at the top (the aperture end), and a flat tertiary mirror inside that directs the light to the eyepiece on the side of the telescope.

Combined with what is called an altitude-azimuth (or "alt-az") mount, the telescope has a focal ratio of f/4.3, making it a fast telescope with a wide field of view. While this doesn't lend itself well to high magnification, its high light-gathering power (due to the large aperture) allows it to display faint objects fairly well.

I began by looking at Saturn while waiting for the evening twilight to fade to black. Saturn is low in the southwest after sunset so to view it you end up looking through a lot of the Earth's atmosphere. This meant that the image was a bit ripply as the heat of the day rose up from the ground through the air, so once it was dark I turned my sights elsewhere.

Nestled in the plane of the Milky Way within the constellation of Sagittarius, the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) and the Swan Nebula (Messier 17) were a bit difficult to distinguish. They appeared as slight grey haze. However, once I added an ultra high contrast filter, these features suddenly popped out from the background and were amazing! Tendrils of gas became visible where none had been before.

Satisfied that the 1-meter could easily see some of the brighter emission nebulae in our northern sky, I shifted to the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), a planetary nebula. Planetary nebulae form when a red giant star gradually sloughs off its outer layers of gas, exposing the hot core. This remnant core, then called a white dwarf, emits high energy radiation that causes the blown out gas to glow. Located high in the northern sky right now, the Cat's Eye Nebula gave off a pleasing teal color. Since most nebulae simply look grey through the eyepiece, the fact that this one looks teal means it must be quite luminous, providing enough photons to stimulate the color-responsive cones in our eyes. Beautiful!

To put the telescope to the test, I then turned to the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51), a spiral galaxy that is interacting with a nearby smaller galaxy. At first I couldn't locate it, but I knew it had to be visible in such a large telescope so I kept hunting. Finally, I realized that the telescope's alignment must have gotten lost somehow - apparently it does that after awhile - so after resetting the alignment using two nearby stars I quickly and easily found M51. The disk of the galaxy was easily seen, as was the neighboring galaxy, and one prominent spiral arm could be seen extending out to touch its neighbor. This was my first time having observed this galactic pair located some 23 million light-years away and it was surely a sight to indulge one's eyes.

I then fired up the 16-inch telescope and viewed the Dumbbell Nebula (Messier 27), and the Ring Nebula (Messier 57), two more planetary nebulae. These two objects are easily within the grasp of our 16-inch Meade LX200, but the 1-meter wasn't able to observe them due to their location near the zenith. Its drive motors didn't want to set the telescope straight up. However, the view through the 16" was still fantastic.

After doing some preliminary tracking diagnostic tests on the 16-inch, I closed up shop around 12:45 a.m. and headed home. Seeing M8, M17, and M51 all for the first time was a great experience and my next goal is to mount one of our CCD cameras to the telescope for some imaging.

For more information about the SUNY Oneonta Observatory and the 1-meter telescope, visit http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/astronomy.html. Tonight is the final public observing night of the summer, so if you're around town tonight at sunset come on up to College Camp to join us! Check out our fall schedule too, at http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/observing_nights.html.

Happy viewing!

The 1-meter telescope is mounted on a trailer, which makes for convenient travel if one wanted to take it to an event.

This telescope is designed with three mirrors: a primary mirror 1 meter in diameter, a secondary mirror up at the top (the aperture end), and a flat tertiary mirror inside that directs the light to the eyepiece on the side of the telescope.

Combined with what is called an altitude-azimuth (or "alt-az") mount, the telescope has a focal ratio of f/4.3, making it a fast telescope with a wide field of view. While this doesn't lend itself well to high magnification, its high light-gathering power (due to the large aperture) allows it to display faint objects fairly well.

I began by looking at Saturn while waiting for the evening twilight to fade to black. Saturn is low in the southwest after sunset so to view it you end up looking through a lot of the Earth's atmosphere. This meant that the image was a bit ripply as the heat of the day rose up from the ground through the air, so once it was dark I turned my sights elsewhere.

Nestled in the plane of the Milky Way within the constellation of Sagittarius, the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) and the Swan Nebula (Messier 17) were a bit difficult to distinguish. They appeared as slight grey haze. However, once I added an ultra high contrast filter, these features suddenly popped out from the background and were amazing! Tendrils of gas became visible where none had been before.

Satisfied that the 1-meter could easily see some of the brighter emission nebulae in our northern sky, I shifted to the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), a planetary nebula. Planetary nebulae form when a red giant star gradually sloughs off its outer layers of gas, exposing the hot core. This remnant core, then called a white dwarf, emits high energy radiation that causes the blown out gas to glow. Located high in the northern sky right now, the Cat's Eye Nebula gave off a pleasing teal color. Since most nebulae simply look grey through the eyepiece, the fact that this one looks teal means it must be quite luminous, providing enough photons to stimulate the color-responsive cones in our eyes. Beautiful!

To put the telescope to the test, I then turned to the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51), a spiral galaxy that is interacting with a nearby smaller galaxy. At first I couldn't locate it, but I knew it had to be visible in such a large telescope so I kept hunting. Finally, I realized that the telescope's alignment must have gotten lost somehow - apparently it does that after awhile - so after resetting the alignment using two nearby stars I quickly and easily found M51. The disk of the galaxy was easily seen, as was the neighboring galaxy, and one prominent spiral arm could be seen extending out to touch its neighbor. This was my first time having observed this galactic pair located some 23 million light-years away and it was surely a sight to indulge one's eyes.

I then fired up the 16-inch telescope and viewed the Dumbbell Nebula (Messier 27), and the Ring Nebula (Messier 57), two more planetary nebulae. These two objects are easily within the grasp of our 16-inch Meade LX200, but the 1-meter wasn't able to observe them due to their location near the zenith. Its drive motors didn't want to set the telescope straight up. However, the view through the 16" was still fantastic.

After doing some preliminary tracking diagnostic tests on the 16-inch, I closed up shop around 12:45 a.m. and headed home. Seeing M8, M17, and M51 all for the first time was a great experience and my next goal is to mount one of our CCD cameras to the telescope for some imaging.

For more information about the SUNY Oneonta Observatory and the 1-meter telescope, visit http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/astronomy.html. Tonight is the final public observing night of the summer, so if you're around town tonight at sunset come on up to College Camp to join us! Check out our fall schedule too, at http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/observing_nights.html.

Happy viewing!

Monday, August 6, 2012

Mars ho!

Early this morning EDT, NASA landed the largest rover yet onto the planet Mars, the fourth rock from the Sun. The Mars Science Laboratory, containing a car-sized rover named Curiosity, landed in Gale Crater via a sophisticated "sky-crane" technique involving a hovering component that gradually and gently lowered the rover to the surface.

Once it had landed, it beamed back a signal of its success and its first images of the crater surface in black and white:

Color images will come later when the main cameras have been activated. At this point, mission scientists are no doubt chomping at the bit to get the rover moving and exploring. Its primary mission is to determine whether Mars was ever capable of supporting life. While this may seem like an ambitious goal, NASA scientists have tried this type of thing before with the Viking landers so they know what sorts of tests don't work as expected. The Curiosity rover, outfitted with a huge array of instruments, should be able to perform far more complex measurements and analyses to measure the mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and to search for any potential chemical building blocks for life. Orbiting spacecraft had previously identified certain minerals within the crater that may have formed in a watery environment, so Curiosity will study these minerals further. If water did indeed exist to facilitate this mineral formation, then it may have also allowed microbial life to exist within the environment as well. Within the Gale Crater there also exists a mountain roughly 3 miles high named Aeolis Mons that Curiosity intends to investigate.

Mars has drawn the attention and inspired the imagination of humanity for well over 100 years. Since Percival Lowell's time spent at the telescope observing what he believed to be canals made by an intelligent but dying civilization, mankind has wondered about the existence of life on our red neighbor. While the existence of such canals was later dismissed, observations of changing dark features on the Martian surface and a spectrum that mimicked that of chlorophyll seemed to suggest that Mars may be covered with some form of vegetation that changed with the seasons. These observations led to the development of many great science-fiction thrillers, from "The War of the Worlds", written in 1898 by H.G. Wells and adapted into both a terrifying radio program and two movies, to "Invaders from Mars" and "Mars Attacks", people have wondered about the possibility of

hostile life on this mysterious world. Other speculative movies linking life on Mars to life on Earth include "Mission to Mars" and "Red Planet". And let's not forget "John Carter" and "Total Recall." While these movies vary in quality, they all address the idea of sending humans to Mars or being visited by beings from Mars.

While the Mariner missions revealed to us that Mars appears to be a dead planet, it does retain some characteristics that make it somewhat Earth-like. A wispy thin carbon dioxide atmosphere, canyons, mountains, and polar ice caps all bring to mind thoughts of Earth. However, its vast lifeless deserts and cratered surface more closely resemble the Moon. Mineralogical evidence that liquid water may have at one time existed on Mars have motivated mission after mission to explore its surface and look for fossilized evidence of life. Now that we have landed the most sophisticated instrument lab yet, we may be able to finally answer this question once and for all.

You can keep up with the Curiosity rover's progress and scientific findings via the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's website at http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/.

Once it had landed, it beamed back a signal of its success and its first images of the crater surface in black and white:

Color images will come later when the main cameras have been activated. At this point, mission scientists are no doubt chomping at the bit to get the rover moving and exploring. Its primary mission is to determine whether Mars was ever capable of supporting life. While this may seem like an ambitious goal, NASA scientists have tried this type of thing before with the Viking landers so they know what sorts of tests don't work as expected. The Curiosity rover, outfitted with a huge array of instruments, should be able to perform far more complex measurements and analyses to measure the mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and to search for any potential chemical building blocks for life. Orbiting spacecraft had previously identified certain minerals within the crater that may have formed in a watery environment, so Curiosity will study these minerals further. If water did indeed exist to facilitate this mineral formation, then it may have also allowed microbial life to exist within the environment as well. Within the Gale Crater there also exists a mountain roughly 3 miles high named Aeolis Mons that Curiosity intends to investigate.

Mars has drawn the attention and inspired the imagination of humanity for well over 100 years. Since Percival Lowell's time spent at the telescope observing what he believed to be canals made by an intelligent but dying civilization, mankind has wondered about the existence of life on our red neighbor. While the existence of such canals was later dismissed, observations of changing dark features on the Martian surface and a spectrum that mimicked that of chlorophyll seemed to suggest that Mars may be covered with some form of vegetation that changed with the seasons. These observations led to the development of many great science-fiction thrillers, from "The War of the Worlds", written in 1898 by H.G. Wells and adapted into both a terrifying radio program and two movies, to "Invaders from Mars" and "Mars Attacks", people have wondered about the possibility of

hostile life on this mysterious world. Other speculative movies linking life on Mars to life on Earth include "Mission to Mars" and "Red Planet". And let's not forget "John Carter" and "Total Recall." While these movies vary in quality, they all address the idea of sending humans to Mars or being visited by beings from Mars.

While the Mariner missions revealed to us that Mars appears to be a dead planet, it does retain some characteristics that make it somewhat Earth-like. A wispy thin carbon dioxide atmosphere, canyons, mountains, and polar ice caps all bring to mind thoughts of Earth. However, its vast lifeless deserts and cratered surface more closely resemble the Moon. Mineralogical evidence that liquid water may have at one time existed on Mars have motivated mission after mission to explore its surface and look for fossilized evidence of life. Now that we have landed the most sophisticated instrument lab yet, we may be able to finally answer this question once and for all.

You can keep up with the Curiosity rover's progress and scientific findings via the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's website at http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/.

Friday, June 29, 2012

July - a great time to use that new telescope!

With the Venus transit behind us now, it seems that the astronomical skies are "calming down" - at least for now. But that doesn't mean there is nothing to hunt down on any given night. The sky is full of potential targets, whether using binoculars or a telescope, so let's take a look at what is coming up in July.

Unfortunately for you naked-eye viewers, there are no meteor showers scheduled for July. The next one isn't until mid-August (the Perseids). However, with the full moon occurring on July 3, this leaves many of the early and mid-month evenings available for reasonably dark-sky constellation viewing. Mars is currently making the transition into the constellation of Virgo right now, gradually drawing closer to Saturn in the sky. At the same time, these two bright planets are beginning to appear lower and lower in the west as the weeks go on, so be sure to spot them before they are gone.

If you got a new set of nice binoculars or a telescope for Christmas and have been anxiously awaiting those warm summer nights to learn how to use it, this would be a great time to get it out. While you may not yet know what exactly to look at - particularly if your telescope isn't motorized - you can still learn the fine art of star-hopping. Find a star map online (free all-sky maps can be found here) or you could download one of any number of astronomy apps if you have a smartphone and you're ready to go. While your binocs or telescope will show more stars than may appear on your star map, you'll gradually get the hang of locating the next star by comparing relative positions and brightnesses. Nothing in astronomy comes easily, but learning is part of the fun. Once you are a master star-hopper, download maps of the Messier objects and push your equipment to the limit. If you are using binoculars for this, you may wish to purchase a tripod and mount for them to hold them steady.

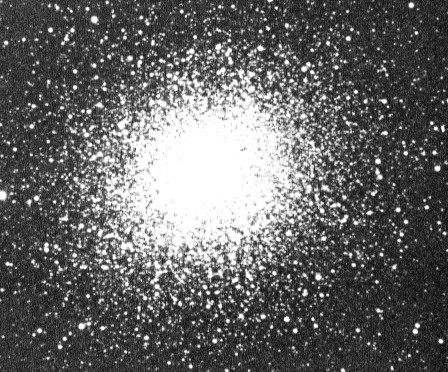

Star clusters are fantastic objects to point your viewing instrument at because they're generally bright enough to see even with small binoculars. The globular cluster M13, for example, is high in the sky all night this month in the constellation of Hercules - hence its unofficial title "The Hercules Cluster." The image below (courtesy of SEDS) will give you an idea of what to expect.

Of course, this is an image taken with a camera so your view through the eyepiece won't be so rich or saturated, but you may find that you prefer the eyepiece view even better! As you examine its stellar population, think about the fact that this cluster is believed to be at least twice as old as our solar system and contains several hundred thousand stars all packed into an area roughly 150 light-years across. Try to count the stars yourself to see how many you can see with your equipment. Imagine what the night sky would look like if you lived on a planet orbiting one of these stars. Then go exploring to see what else you can find!

Happy viewing!

Unfortunately for you naked-eye viewers, there are no meteor showers scheduled for July. The next one isn't until mid-August (the Perseids). However, with the full moon occurring on July 3, this leaves many of the early and mid-month evenings available for reasonably dark-sky constellation viewing. Mars is currently making the transition into the constellation of Virgo right now, gradually drawing closer to Saturn in the sky. At the same time, these two bright planets are beginning to appear lower and lower in the west as the weeks go on, so be sure to spot them before they are gone.

If you got a new set of nice binoculars or a telescope for Christmas and have been anxiously awaiting those warm summer nights to learn how to use it, this would be a great time to get it out. While you may not yet know what exactly to look at - particularly if your telescope isn't motorized - you can still learn the fine art of star-hopping. Find a star map online (free all-sky maps can be found here) or you could download one of any number of astronomy apps if you have a smartphone and you're ready to go. While your binocs or telescope will show more stars than may appear on your star map, you'll gradually get the hang of locating the next star by comparing relative positions and brightnesses. Nothing in astronomy comes easily, but learning is part of the fun. Once you are a master star-hopper, download maps of the Messier objects and push your equipment to the limit. If you are using binoculars for this, you may wish to purchase a tripod and mount for them to hold them steady.

Star clusters are fantastic objects to point your viewing instrument at because they're generally bright enough to see even with small binoculars. The globular cluster M13, for example, is high in the sky all night this month in the constellation of Hercules - hence its unofficial title "The Hercules Cluster." The image below (courtesy of SEDS) will give you an idea of what to expect.

Of course, this is an image taken with a camera so your view through the eyepiece won't be so rich or saturated, but you may find that you prefer the eyepiece view even better! As you examine its stellar population, think about the fact that this cluster is believed to be at least twice as old as our solar system and contains several hundred thousand stars all packed into an area roughly 150 light-years across. Try to count the stars yourself to see how many you can see with your equipment. Imagine what the night sky would look like if you lived on a planet orbiting one of these stars. Then go exploring to see what else you can find!

Happy viewing!

Friday, June 8, 2012

Venus Transit, Conquered

Oneonta weather gave us some challenges when it came time to observe the last Venus transit for 105 years, but it was worth it! This entry is a description of the evening's event as I described it to the folks who write for the College news.

The evening began with a solid cloud deck and rain, but by 6:00 the rain had stopped and the clouds had slightly thinned. By that point, Shawn Grove (a 2012 SUNY Oneonta graduate) and I were joined by 5 or 6 people from the community in the observatory waiting for the weather to clear. The transit technically began at 6:03 p.m. here in Oneonta, and around 6:10 we were suddenly greeted with a thin spot in the clouds where we could see the disk of the Sun. Quickly we pointed the 14-inch telescope at it and were greeted with a view showing Venus approximately halfway through its "entrance" into the solar disk. It looked like a dark dimple in the edge of the Sun. Those who were present were very excited to see this, although it only lasted a few minutes before the clouds thickened up again. From then we waited for over an hour, watching as small gaps in the clouds passed by outside the vicinity of the Sun. More people from the community arrived, and some waited while others left.

Then at about 7:20 p.m. we saw sunlight streaming through another break in the clouds. By this time the Sun had dropped low enough that it was behind trees, so we couldn't see it from the elevated 14-inch dome. However, we did have a smaller 4.5-inch telescope with a solar filter on the ground that we could move. Grabbing it, we raced across the grassy lawn to a point where the Sun was visible. Venus was well into its transit by then so we were blessed with the view that is shown in the image below.

The clouds remained thin enough to see it clearly while the group of roughly 15 people, including several children, each took turns looking through the small scope. A handful of people had gone into the woods to check out the nearby pond and when we called out to them they came sprinting out of the woods. Everyone was able to see it, many people took pictures with camera phones (and me with my digital camera), and by 7:45 p.m. the clouds obscured the Sun again just as it dropped below the tree line for good.

Part of the excitement was that "thrill of the hunt" feeling from waiting and then pursuing with the small telescope in hand. Another part of the excitement came from being able to witness an event that won't occur for another 105 years. However, I think the greatest satisfaction for me was being able to see people from the community come up in the hopes of seeing the transit, be rewarded for their diligence, and walk away feeling like it had been worth the wait. Everyone was thrilled to have been able to see it. Thank you to everyone who came out to see it!

The evening began with a solid cloud deck and rain, but by 6:00 the rain had stopped and the clouds had slightly thinned. By that point, Shawn Grove (a 2012 SUNY Oneonta graduate) and I were joined by 5 or 6 people from the community in the observatory waiting for the weather to clear. The transit technically began at 6:03 p.m. here in Oneonta, and around 6:10 we were suddenly greeted with a thin spot in the clouds where we could see the disk of the Sun. Quickly we pointed the 14-inch telescope at it and were greeted with a view showing Venus approximately halfway through its "entrance" into the solar disk. It looked like a dark dimple in the edge of the Sun. Those who were present were very excited to see this, although it only lasted a few minutes before the clouds thickened up again. From then we waited for over an hour, watching as small gaps in the clouds passed by outside the vicinity of the Sun. More people from the community arrived, and some waited while others left.

Then at about 7:20 p.m. we saw sunlight streaming through another break in the clouds. By this time the Sun had dropped low enough that it was behind trees, so we couldn't see it from the elevated 14-inch dome. However, we did have a smaller 4.5-inch telescope with a solar filter on the ground that we could move. Grabbing it, we raced across the grassy lawn to a point where the Sun was visible. Venus was well into its transit by then so we were blessed with the view that is shown in the image below.

The clouds remained thin enough to see it clearly while the group of roughly 15 people, including several children, each took turns looking through the small scope. A handful of people had gone into the woods to check out the nearby pond and when we called out to them they came sprinting out of the woods. Everyone was able to see it, many people took pictures with camera phones (and me with my digital camera), and by 7:45 p.m. the clouds obscured the Sun again just as it dropped below the tree line for good.

Part of the excitement was that "thrill of the hunt" feeling from waiting and then pursuing with the small telescope in hand. Another part of the excitement came from being able to witness an event that won't occur for another 105 years. However, I think the greatest satisfaction for me was being able to see people from the community come up in the hopes of seeing the transit, be rewarded for their diligence, and walk away feeling like it had been worth the wait. Everyone was thrilled to have been able to see it. Thank you to everyone who came out to see it!

Monday, June 4, 2012

Venus Transit of the Century

With a plethora of websites dedicated to tomorrow's transit of Venus across the face of the Sun, including a page on Wikipedia about it, I don't feel the need to wax eloquent about the upcoming event in too much detail. Numerous sources can be read to learn about the orbits of Venus and Earth, the importance it once had in determining the distance scales of our solar system, and so on. However, since this blog is dedicated to the observer in the Oneonta, NY region, you're probably wondering about when it will be visible.

The most recent transit of Venus occurred in early June of 2004. This transit occurred in the early morning in North America, with viewers in New York seeing it already in progress as the sun rose. This made the event a bit of a challenge to see, since getting up before the sun rises isn't on most people's list of favorite things to do. In Michigan at this time, I would have been an undergraduate at Central Michigan University. Since I was an avid astronomer and astronomy student at the time, if it had been visible then I'm sure I would have gone to see it at our school's telescope. The fact that I don't have any memories of it makes me think it may have been cloudy that day.

For those who don't know me...I have a terrible memory. Case in point: I currently have 13 Post-it notes on my desk at this very moment with reminders for various things! Not to mention the five half-page sized pieces of paper with other various notes jotted on them and an index card of notes as well. But I digress...

The 2012 Venus is visible in North America in the early evening until sunset, making it much more accessible for the average viewer. Expected to begin at approximately 6:00 p.m. in Oneonta, the second planet from the Sun (and our closest planetary neighbor) will continue its sojourn across our star's face until well after the sun has set, giving us only a limited opportunity to watch it for approximately an hour and a half.

The current weather forecast is for clouds and possibly rain. If you're a sucker for "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunities, you may want to take a trip somewhere else to watch it - preferably farther west where you can watch it for a longer time period.

HOWEVER! The Internet now offers the couch-astronomer and those of us in cloudy parts of the planet the chance to watch this event live as seen from somewhere else. You can visit the website for the SLOOH Space Camera or NASA's live webcast from Mauna Kea, Hawaii. I recommend tuning into the webcast shortly before 6:00 p.m. EDT to make sure you see it. If you want it to feel like you're really there watching it through a telescope, get a paper towel tube and hold it up to your computer screen. Who says you need fancy equipment? The Internet is pretty fancy in my opinion!

If you are in the Oneonta area and the weather magically happens to be clear in the late afternoon on June 5, come see us at the SUNY Oneonta observatory at College Camp. We will have a couple telescopes with solar filters for safe viewing set up. Don't look directly at the sun for this event, or permanent eye damage may result. We will have safe equipment for viewing the event. Our viewing of the Sun and the eclipse will be open to the public starting at 5:30 p.m.

If the weather looks bad, hop online and visit one of the websites above. This is what I did for the most recent annular solar eclipse and it wasn't bad. Better than missing it altogether, anyway!

Happy viewing!

The most recent transit of Venus occurred in early June of 2004. This transit occurred in the early morning in North America, with viewers in New York seeing it already in progress as the sun rose. This made the event a bit of a challenge to see, since getting up before the sun rises isn't on most people's list of favorite things to do. In Michigan at this time, I would have been an undergraduate at Central Michigan University. Since I was an avid astronomer and astronomy student at the time, if it had been visible then I'm sure I would have gone to see it at our school's telescope. The fact that I don't have any memories of it makes me think it may have been cloudy that day.

For those who don't know me...I have a terrible memory. Case in point: I currently have 13 Post-it notes on my desk at this very moment with reminders for various things! Not to mention the five half-page sized pieces of paper with other various notes jotted on them and an index card of notes as well. But I digress...

The 2012 Venus is visible in North America in the early evening until sunset, making it much more accessible for the average viewer. Expected to begin at approximately 6:00 p.m. in Oneonta, the second planet from the Sun (and our closest planetary neighbor) will continue its sojourn across our star's face until well after the sun has set, giving us only a limited opportunity to watch it for approximately an hour and a half.

The current weather forecast is for clouds and possibly rain. If you're a sucker for "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunities, you may want to take a trip somewhere else to watch it - preferably farther west where you can watch it for a longer time period.

HOWEVER! The Internet now offers the couch-astronomer and those of us in cloudy parts of the planet the chance to watch this event live as seen from somewhere else. You can visit the website for the SLOOH Space Camera or NASA's live webcast from Mauna Kea, Hawaii. I recommend tuning into the webcast shortly before 6:00 p.m. EDT to make sure you see it. If you want it to feel like you're really there watching it through a telescope, get a paper towel tube and hold it up to your computer screen. Who says you need fancy equipment? The Internet is pretty fancy in my opinion!

If you are in the Oneonta area and the weather magically happens to be clear in the late afternoon on June 5, come see us at the SUNY Oneonta observatory at College Camp. We will have a couple telescopes with solar filters for safe viewing set up. Don't look directly at the sun for this event, or permanent eye damage may result. We will have safe equipment for viewing the event. Our viewing of the Sun and the eclipse will be open to the public starting at 5:30 p.m.

If the weather looks bad, hop online and visit one of the websites above. This is what I did for the most recent annular solar eclipse and it wasn't bad. Better than missing it altogether, anyway!

Happy viewing!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)