As I peruse recent issues of Astronomy magazine I can't help but wonder if the newest technologically-advanced amateur telescopes are actually ruining stargazing. We live in a very fast-paced, instant-reward world where it's easy to expect, or even feel entitled, to get results without the work. The newest motorized telescopes are now coming equipped with built-in digital cameras that automatically take images of the night sky and compare them to their internal databases, allowing it to figure out where on Earth it's located without human input. This means that the user no longer needs to learn how to align their telescope because it will do it on its own.

I get that aligning the telescope can be a pain, particularly if it isn't computerized at all. Once the telescope auto-aligns, it then provides the user with access to a built-in catalog of thousands of night-sky objects that can be found with the click of a button. This means that the user no longer needs to know how to read a star map or locate objects by hand - the telescope finds them automatically and (provided that its auto-alignment went well) the user is rewarded.

Does this help the novice access the night sky? Yes. Does it make it faster to find an object when you're doing a public viewing or star party? Absolutely. But I also believe it acts as a crutch that is too easy to lean on to resist. You don't need to have a mental concept of the celestial sphere, or even be able to identify the location of Pegasus, anymore. Just turn it on, wait a minute, then type in your object. Is it even above the horizon? Who knows, but the computer will tell you! I'm predicting that the next-generation telescope will collimate itself, focus itself, and even have a built-in zoom eyepiece that magnifies and focuses on command. Maybe it'll even have a coffee-maker built in to keep you warm!

I'm a purist, I suppose. The only camera I want is for imaging my target, the only computer I need is one back inside for processing the data afterward. Instant gratification is providing us with the tools to never have to think again, never have to wait too long, and not know how to fix something if anything goes wrong. Grumble, grumble, grumble...oh but it sure is fancy and easy to use! Yes, part of me has great disdain for such a crutch, while another part of me still wants to use it so I don't have to do the darn alignment myself.

Okay, I'm climbing off my soap box, stashing my crotchetiness in my desk drawer, and getting back into the normal mode!

Jupiter is looking wonderful this month. As we approach opposition, the planet is visible all night long and is wonderfully big and bright. Once Taurus rises in the evening, Jupiter is easily spotted as the brightest object around (unless you're looking at the Moon). Keeping track of Jupiter's Great Red Spot is a good test of your optical equipment, and fortunately Sky & Telescope provides a great tool for identifying when it will be visible on a given day. Observing a jovian moon transit (Io passes in front of the king of planets just after midnight EST on the night of December 7/8) is also rewarding for the perspective it provides.

Imagine standing on the surface of Io and looking up at Jupiter dominating your sky! Or better yet, visit Jeff Bryant's website that contains his artistic renderings of this scene, and a multitude of others.

Last month at the public observing night I had the opportunity to view NGC 7009 (the "Saturn Nebula") through the 16-inch and it looked great. There is something very fulfilling about viewing a new object every month. If you have a moderate-sized telescope, give it a try. It's in Aquarius, though, so don't wait too long into the night.

For those of you who are curious...yes, I used the telescope's computer control paddle to find the nebula. I don't have all night ;-)

Happy viewing!

A guide to keep you informed about the night sky over Oneonta, NY, brought to you by the astronomer at the SUNY College at Oneonta.

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Friday, November 2, 2012

The Oneonta Stargazer is now on Twitter!

If you're interested in keeping up with the observing conditions at the SUNY Oneonta Observatory, located at College Camp just north of campus, then you can follow us on Twitter:

Follow @OneontaStargaze

Yes, I know, this blog is called "Oneonta Stargazer" while the Twitter handle is "OneontaStargaze." It turns out, there is a character limit in the length of a Twitter handle and I figured it was easier to tell people "OneontaStargaze" rather than try for "OneontaStargazr" and explain that the last 'e' is missing. So, there it is.

Here I will post updates regarding the status of any public observing nights in real-time, and any other updates that are astronomy-related as well. Follow the Oneonta Stargazer on Twitter!

Follow @OneontaStargaze

Yes, I know, this blog is called "Oneonta Stargazer" while the Twitter handle is "OneontaStargaze." It turns out, there is a character limit in the length of a Twitter handle and I figured it was easier to tell people "OneontaStargaze" rather than try for "OneontaStargazr" and explain that the last 'e' is missing. So, there it is.

Here I will post updates regarding the status of any public observing nights in real-time, and any other updates that are astronomy-related as well. Follow the Oneonta Stargazer on Twitter!

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Jovian transits

Jupiter has been on the rise earlier and earlier each evening lately. Look for it peeking above the eastern horizon after 8:00 p.m. (EDT) tonight - but don't confuse it for the reddish-orange star Aldebaran right next to it!

With binoculars or a telescope you can see the four Galilean moons, those moons observed by Galileo when he first turned a telescope toward the stars, as they continue their eternal march around the king of planets. While these moons all orbit along the same general plane, and this plane is mostly oriented along our line of sight, catching any one of these moons in the act of being anywhere but off to the side is challenging. However, on November 7th we get just such an opportunity as the volcanic moon Io ("eye-oh") can be seen transiting its host planet that evening. This event actually reoccurs on November 30, in case you miss it on the 7th. During these two transits, the shadow of Io appears first against the disk of Jupiter because we have not yet passed Jupiter in our orbit around the Sun:

The shadow being cast by Io extends straight back away from the Sun, but because we are viewing the alignment from an angle we see the shadow cross in front of Jupiter first, then Io appears soon after. The shadow makes its first appearance at 10:11 pm EST (NOTE: daylight savings time ends this weekend, so when you're viewing the transit you will be on standard time). Io the crosses against the jovian disk about a half hour later. In case it's cloudy that night, you can see the same event happen again on Nov 30, with the shadow's first appearance at 10:22 pm EST, with Io appearing only about 5 minutes later. This difference in appearance delays reflects the fact that our viewing angle is shrinking as Jupiter approaches opposition (actually, it's due to our movement, not Jupiter's). If the transit occurred exactly at opposition, both the shadow and Io would appear at the same time. Viewed from Earth with a modest telescope, Io will be very difficult to see - so look for the shadow instead.

If it's cloudy both nights, then check out this nice NASA image of a transit as viewed by the Hubble Space Telescope and pretend you're watching it happen live.

I for one will be hoping it is clear that night so I can watch it from the SUNY Oneonta observatory with my students, who will (hopefully) be enjoying an outdoor lab that night.

Happy viewing!

Thursday, October 11, 2012

One meteor shower after another

Wow! Suddenly a whole month has passed since my last post. How time flies once the college semester begins. I think I'm going to need to develop a reminder system so such a delay doesn't reoccur...

This fall has been remarkable for the number of clear nights - except on nights when celestial events are happening, of course. The Draconid meteor shower peaked over the weekend and according to those who observed it there was a fairly significant outburst during the peak, up to a rate of hundreds per hour. Here in Oneonta, it was cloudy. There was also a solar flare that produced northern lights visible as far south as Kansas, but here in Oneonta it was cloudy. Such is life. There is a prediction for moderate aurora activity on Oct. 14-15, when a coronal hole on the Sun rotates Earthward. Keep your eyes peeled!

So what's coming up that is worth checking out? Another meteor shower! The Orionid meteor shower peaks during the night of October 20/21. Like the Eta Aquariid meteor shower earlier this spring, the Orionis meteor shower also results from debris left behind by Halley's Comet. Its name comes from the fact that its radiant, the point from which the meteors appear to originate, lies in the constellation Orion.

The view looking east as Orion rises on the night of Oct. 20/21, seen at 11:30 p.m. EDT.

This meteor shower typically produces around 20 meteors per hour, though it can peak at 60 per hour on good years. During the few days leading up to the 20th and the few days afterward, occasional meteors can be seen as activity rises up to the peak and drops off afterward. Although the radiant is located in Orion, it's actually better to look roughly 90 degrees away from the radiant. This provides the best opportunity to see those meteors that give us a glancing blow, rather than the ones that travel more-or-less right at the viewer. I recommend facing east and looking up. It'll be cold out there, so bundle up! And while you're looking, check out Jupiter.

As a foreshadowing of things to come, next year looks great for comet viewing. Two new comets have recently been discovered that could shine bright enough to be seen with the naked eye! C/2012 S1 (ISON) and C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) will be two comets to keep up with as they rapidly close their distance between themselves and the Sun. It is thought that neither comet has made an approach to the Sun before, meaning there could be a lot of frozen ice and gas present to put on a show as it sublimates into space.

Happy viewing!

This fall has been remarkable for the number of clear nights - except on nights when celestial events are happening, of course. The Draconid meteor shower peaked over the weekend and according to those who observed it there was a fairly significant outburst during the peak, up to a rate of hundreds per hour. Here in Oneonta, it was cloudy. There was also a solar flare that produced northern lights visible as far south as Kansas, but here in Oneonta it was cloudy. Such is life. There is a prediction for moderate aurora activity on Oct. 14-15, when a coronal hole on the Sun rotates Earthward. Keep your eyes peeled!

So what's coming up that is worth checking out? Another meteor shower! The Orionid meteor shower peaks during the night of October 20/21. Like the Eta Aquariid meteor shower earlier this spring, the Orionis meteor shower also results from debris left behind by Halley's Comet. Its name comes from the fact that its radiant, the point from which the meteors appear to originate, lies in the constellation Orion.

The view looking east as Orion rises on the night of Oct. 20/21, seen at 11:30 p.m. EDT.

This meteor shower typically produces around 20 meteors per hour, though it can peak at 60 per hour on good years. During the few days leading up to the 20th and the few days afterward, occasional meteors can be seen as activity rises up to the peak and drops off afterward. Although the radiant is located in Orion, it's actually better to look roughly 90 degrees away from the radiant. This provides the best opportunity to see those meteors that give us a glancing blow, rather than the ones that travel more-or-less right at the viewer. I recommend facing east and looking up. It'll be cold out there, so bundle up! And while you're looking, check out Jupiter.

As a foreshadowing of things to come, next year looks great for comet viewing. Two new comets have recently been discovered that could shine bright enough to be seen with the naked eye! C/2012 S1 (ISON) and C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) will be two comets to keep up with as they rapidly close their distance between themselves and the Sun. It is thought that neither comet has made an approach to the Sun before, meaning there could be a lot of frozen ice and gas present to put on a show as it sublimates into space.

Happy viewing!

Friday, September 14, 2012

Where are all the planets?

The last few nights here in Oneonta have been just spectacular! No wind, no clouds, no haze, steady seeing, and reasonable temperatures. The astronomer can't ask for circumstances better than these. If you stepped outside during the evening, however, you may have asked yourself one question.

Where did all the planets go?

We've been treated to a plethora of planets this summer: Jupiter and Venus were around during the early summer until our sister planet's transit in early June. Then Saturn and Mars were the stars of the show during their conjunction in the late portion of the summer. However, they too have now drifted down into the glow of the sunset as the ecliptic (the path the Sun traces out through the sky and the path that the planets closely follow) dips low at a shallow angle in the southern sky...and we are left with nothing for the time being.

So when will the planets return? Unfortunately, the remainder of September offers us nothing but an opportunity to exercise patience as October approaches. For those who don't mind staying up past midnight, Jupiter rises in the east with Taurus and Orion, and Venus rises shortly before the Sun, but for those of you who cherish your hours of sleep, there are no opportunities for several weeks yet.

What, then, is a person supposed to view at night if the planets are nowhere to be seen and the Moon is in its New Phase (which occurs in a couple days)? This might be an excellent time to re-familiarize yourself with the constellations of the early autumn sky. Ursa Major dips low in the north right now, so you may need to use Cassiopeia to locate the North Star.

High above your head lies the three bright stars that form the asterism called the Summer Triangle. Named Vega, Deneb, and Altair, these stars form an isosceles triangle that points generally in a southern direction for most of the night, with Altair at the southern tip. However, it is a constellation adjacent (in the east) to the Summer Triangle that leads us to our object of interest. Rising in the east before sunset is the "Great Square" of Pegasus, the flying horse. Flying upside-down, this horse rises head and front legs first, with its square body coming next. Along the northeastern horizon, two trails of stars that look like its rear legs rise with it.

However, these rear legs actually comprise the constellation of Andromeda. These two trails of stars represent the princess rescued by Perseus from the jaws of the great sea monster Cetus. Within this constellation lies the Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

This galaxy is one of our Milky Way Galaxy's closest neighbors, lying a scant 2.5 million light-years away. Resembling the Milky Way in both its spiral shape and size, the Andromeda Galaxy is currently hurtling toward the Milky Way at breakneck speed, destined for collision some 5 billion years from now. This NASA website about the upcoming collision contains some nice images and video simulating the night sky as the intersection approaches. While it is described as a collision, the large distances between stars in both galaxies mean that they will more-or-less pass through each other at first, with few to none actual stellar collisions. Gravity's ceaseless pull will then cause them to double back on each other and ultimately merge together to form a large elliptical galaxy. Gas clouds will light up with star formation. If anyone is alive to witness the event, it should be spectacular - though there is a nonzero chance of that witness' home planet being flung out of the galaxy altogether or traded from one to the other during the first couple passes through. How cool would it be to live in the Milky Way Galaxy at first and then get traded to the Andromeda Galaxy as they interact with each other?!

If you have binoculars or a telescope, turn them to the Andromeda Galaxy and ponder this future. Practice star-hopping from Beta Andromedae to Mu Andromedae to Nu Andromedae and ultimately to M31. Getting to know where these objects are is half the fun!

Happy viewing!

Where did all the planets go?

We've been treated to a plethora of planets this summer: Jupiter and Venus were around during the early summer until our sister planet's transit in early June. Then Saturn and Mars were the stars of the show during their conjunction in the late portion of the summer. However, they too have now drifted down into the glow of the sunset as the ecliptic (the path the Sun traces out through the sky and the path that the planets closely follow) dips low at a shallow angle in the southern sky...and we are left with nothing for the time being.

So when will the planets return? Unfortunately, the remainder of September offers us nothing but an opportunity to exercise patience as October approaches. For those who don't mind staying up past midnight, Jupiter rises in the east with Taurus and Orion, and Venus rises shortly before the Sun, but for those of you who cherish your hours of sleep, there are no opportunities for several weeks yet.

What, then, is a person supposed to view at night if the planets are nowhere to be seen and the Moon is in its New Phase (which occurs in a couple days)? This might be an excellent time to re-familiarize yourself with the constellations of the early autumn sky. Ursa Major dips low in the north right now, so you may need to use Cassiopeia to locate the North Star.

High above your head lies the three bright stars that form the asterism called the Summer Triangle. Named Vega, Deneb, and Altair, these stars form an isosceles triangle that points generally in a southern direction for most of the night, with Altair at the southern tip. However, it is a constellation adjacent (in the east) to the Summer Triangle that leads us to our object of interest. Rising in the east before sunset is the "Great Square" of Pegasus, the flying horse. Flying upside-down, this horse rises head and front legs first, with its square body coming next. Along the northeastern horizon, two trails of stars that look like its rear legs rise with it.

However, these rear legs actually comprise the constellation of Andromeda. These two trails of stars represent the princess rescued by Perseus from the jaws of the great sea monster Cetus. Within this constellation lies the Andromeda Galaxy, M31.

This galaxy is one of our Milky Way Galaxy's closest neighbors, lying a scant 2.5 million light-years away. Resembling the Milky Way in both its spiral shape and size, the Andromeda Galaxy is currently hurtling toward the Milky Way at breakneck speed, destined for collision some 5 billion years from now. This NASA website about the upcoming collision contains some nice images and video simulating the night sky as the intersection approaches. While it is described as a collision, the large distances between stars in both galaxies mean that they will more-or-less pass through each other at first, with few to none actual stellar collisions. Gravity's ceaseless pull will then cause them to double back on each other and ultimately merge together to form a large elliptical galaxy. Gas clouds will light up with star formation. If anyone is alive to witness the event, it should be spectacular - though there is a nonzero chance of that witness' home planet being flung out of the galaxy altogether or traded from one to the other during the first couple passes through. How cool would it be to live in the Milky Way Galaxy at first and then get traded to the Andromeda Galaxy as they interact with each other?!

If you have binoculars or a telescope, turn them to the Andromeda Galaxy and ponder this future. Practice star-hopping from Beta Andromedae to Mu Andromedae to Nu Andromedae and ultimately to M31. Getting to know where these objects are is half the fun!

Happy viewing!

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

The SUNY Oneonta 1-meter Telescope

With the Clear Sky Chart indicating two clear nights in a row, I decided to get out the 1-meter telescope owned by SUNY Oneonta to do some observing tests before tonight's public viewing. As evening approached, I was joined by some local wildlife:

The 1-meter telescope is mounted on a trailer, which makes for convenient travel if one wanted to take it to an event.

This telescope is designed with three mirrors: a primary mirror 1 meter in diameter, a secondary mirror up at the top (the aperture end), and a flat tertiary mirror inside that directs the light to the eyepiece on the side of the telescope.

Combined with what is called an altitude-azimuth (or "alt-az") mount, the telescope has a focal ratio of f/4.3, making it a fast telescope with a wide field of view. While this doesn't lend itself well to high magnification, its high light-gathering power (due to the large aperture) allows it to display faint objects fairly well.

I began by looking at Saturn while waiting for the evening twilight to fade to black. Saturn is low in the southwest after sunset so to view it you end up looking through a lot of the Earth's atmosphere. This meant that the image was a bit ripply as the heat of the day rose up from the ground through the air, so once it was dark I turned my sights elsewhere.

Nestled in the plane of the Milky Way within the constellation of Sagittarius, the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) and the Swan Nebula (Messier 17) were a bit difficult to distinguish. They appeared as slight grey haze. However, once I added an ultra high contrast filter, these features suddenly popped out from the background and were amazing! Tendrils of gas became visible where none had been before.

Satisfied that the 1-meter could easily see some of the brighter emission nebulae in our northern sky, I shifted to the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), a planetary nebula. Planetary nebulae form when a red giant star gradually sloughs off its outer layers of gas, exposing the hot core. This remnant core, then called a white dwarf, emits high energy radiation that causes the blown out gas to glow. Located high in the northern sky right now, the Cat's Eye Nebula gave off a pleasing teal color. Since most nebulae simply look grey through the eyepiece, the fact that this one looks teal means it must be quite luminous, providing enough photons to stimulate the color-responsive cones in our eyes. Beautiful!

To put the telescope to the test, I then turned to the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51), a spiral galaxy that is interacting with a nearby smaller galaxy. At first I couldn't locate it, but I knew it had to be visible in such a large telescope so I kept hunting. Finally, I realized that the telescope's alignment must have gotten lost somehow - apparently it does that after awhile - so after resetting the alignment using two nearby stars I quickly and easily found M51. The disk of the galaxy was easily seen, as was the neighboring galaxy, and one prominent spiral arm could be seen extending out to touch its neighbor. This was my first time having observed this galactic pair located some 23 million light-years away and it was surely a sight to indulge one's eyes.

I then fired up the 16-inch telescope and viewed the Dumbbell Nebula (Messier 27), and the Ring Nebula (Messier 57), two more planetary nebulae. These two objects are easily within the grasp of our 16-inch Meade LX200, but the 1-meter wasn't able to observe them due to their location near the zenith. Its drive motors didn't want to set the telescope straight up. However, the view through the 16" was still fantastic.

After doing some preliminary tracking diagnostic tests on the 16-inch, I closed up shop around 12:45 a.m. and headed home. Seeing M8, M17, and M51 all for the first time was a great experience and my next goal is to mount one of our CCD cameras to the telescope for some imaging.

For more information about the SUNY Oneonta Observatory and the 1-meter telescope, visit http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/astronomy.html. Tonight is the final public observing night of the summer, so if you're around town tonight at sunset come on up to College Camp to join us! Check out our fall schedule too, at http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/observing_nights.html.

Happy viewing!

The 1-meter telescope is mounted on a trailer, which makes for convenient travel if one wanted to take it to an event.

This telescope is designed with three mirrors: a primary mirror 1 meter in diameter, a secondary mirror up at the top (the aperture end), and a flat tertiary mirror inside that directs the light to the eyepiece on the side of the telescope.

Combined with what is called an altitude-azimuth (or "alt-az") mount, the telescope has a focal ratio of f/4.3, making it a fast telescope with a wide field of view. While this doesn't lend itself well to high magnification, its high light-gathering power (due to the large aperture) allows it to display faint objects fairly well.

I began by looking at Saturn while waiting for the evening twilight to fade to black. Saturn is low in the southwest after sunset so to view it you end up looking through a lot of the Earth's atmosphere. This meant that the image was a bit ripply as the heat of the day rose up from the ground through the air, so once it was dark I turned my sights elsewhere.

Nestled in the plane of the Milky Way within the constellation of Sagittarius, the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) and the Swan Nebula (Messier 17) were a bit difficult to distinguish. They appeared as slight grey haze. However, once I added an ultra high contrast filter, these features suddenly popped out from the background and were amazing! Tendrils of gas became visible where none had been before.

Satisfied that the 1-meter could easily see some of the brighter emission nebulae in our northern sky, I shifted to the Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), a planetary nebula. Planetary nebulae form when a red giant star gradually sloughs off its outer layers of gas, exposing the hot core. This remnant core, then called a white dwarf, emits high energy radiation that causes the blown out gas to glow. Located high in the northern sky right now, the Cat's Eye Nebula gave off a pleasing teal color. Since most nebulae simply look grey through the eyepiece, the fact that this one looks teal means it must be quite luminous, providing enough photons to stimulate the color-responsive cones in our eyes. Beautiful!

To put the telescope to the test, I then turned to the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51), a spiral galaxy that is interacting with a nearby smaller galaxy. At first I couldn't locate it, but I knew it had to be visible in such a large telescope so I kept hunting. Finally, I realized that the telescope's alignment must have gotten lost somehow - apparently it does that after awhile - so after resetting the alignment using two nearby stars I quickly and easily found M51. The disk of the galaxy was easily seen, as was the neighboring galaxy, and one prominent spiral arm could be seen extending out to touch its neighbor. This was my first time having observed this galactic pair located some 23 million light-years away and it was surely a sight to indulge one's eyes.

I then fired up the 16-inch telescope and viewed the Dumbbell Nebula (Messier 27), and the Ring Nebula (Messier 57), two more planetary nebulae. These two objects are easily within the grasp of our 16-inch Meade LX200, but the 1-meter wasn't able to observe them due to their location near the zenith. Its drive motors didn't want to set the telescope straight up. However, the view through the 16" was still fantastic.

After doing some preliminary tracking diagnostic tests on the 16-inch, I closed up shop around 12:45 a.m. and headed home. Seeing M8, M17, and M51 all for the first time was a great experience and my next goal is to mount one of our CCD cameras to the telescope for some imaging.

For more information about the SUNY Oneonta Observatory and the 1-meter telescope, visit http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/astronomy.html. Tonight is the final public observing night of the summer, so if you're around town tonight at sunset come on up to College Camp to join us! Check out our fall schedule too, at http://employees.oneonta.edu/smolinjp/observing_nights.html.

Happy viewing!

Monday, August 6, 2012

Mars ho!

Early this morning EDT, NASA landed the largest rover yet onto the planet Mars, the fourth rock from the Sun. The Mars Science Laboratory, containing a car-sized rover named Curiosity, landed in Gale Crater via a sophisticated "sky-crane" technique involving a hovering component that gradually and gently lowered the rover to the surface.

Once it had landed, it beamed back a signal of its success and its first images of the crater surface in black and white:

Color images will come later when the main cameras have been activated. At this point, mission scientists are no doubt chomping at the bit to get the rover moving and exploring. Its primary mission is to determine whether Mars was ever capable of supporting life. While this may seem like an ambitious goal, NASA scientists have tried this type of thing before with the Viking landers so they know what sorts of tests don't work as expected. The Curiosity rover, outfitted with a huge array of instruments, should be able to perform far more complex measurements and analyses to measure the mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and to search for any potential chemical building blocks for life. Orbiting spacecraft had previously identified certain minerals within the crater that may have formed in a watery environment, so Curiosity will study these minerals further. If water did indeed exist to facilitate this mineral formation, then it may have also allowed microbial life to exist within the environment as well. Within the Gale Crater there also exists a mountain roughly 3 miles high named Aeolis Mons that Curiosity intends to investigate.

Mars has drawn the attention and inspired the imagination of humanity for well over 100 years. Since Percival Lowell's time spent at the telescope observing what he believed to be canals made by an intelligent but dying civilization, mankind has wondered about the existence of life on our red neighbor. While the existence of such canals was later dismissed, observations of changing dark features on the Martian surface and a spectrum that mimicked that of chlorophyll seemed to suggest that Mars may be covered with some form of vegetation that changed with the seasons. These observations led to the development of many great science-fiction thrillers, from "The War of the Worlds", written in 1898 by H.G. Wells and adapted into both a terrifying radio program and two movies, to "Invaders from Mars" and "Mars Attacks", people have wondered about the possibility of

hostile life on this mysterious world. Other speculative movies linking life on Mars to life on Earth include "Mission to Mars" and "Red Planet". And let's not forget "John Carter" and "Total Recall." While these movies vary in quality, they all address the idea of sending humans to Mars or being visited by beings from Mars.

While the Mariner missions revealed to us that Mars appears to be a dead planet, it does retain some characteristics that make it somewhat Earth-like. A wispy thin carbon dioxide atmosphere, canyons, mountains, and polar ice caps all bring to mind thoughts of Earth. However, its vast lifeless deserts and cratered surface more closely resemble the Moon. Mineralogical evidence that liquid water may have at one time existed on Mars have motivated mission after mission to explore its surface and look for fossilized evidence of life. Now that we have landed the most sophisticated instrument lab yet, we may be able to finally answer this question once and for all.

You can keep up with the Curiosity rover's progress and scientific findings via the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's website at http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/.

Once it had landed, it beamed back a signal of its success and its first images of the crater surface in black and white:

Color images will come later when the main cameras have been activated. At this point, mission scientists are no doubt chomping at the bit to get the rover moving and exploring. Its primary mission is to determine whether Mars was ever capable of supporting life. While this may seem like an ambitious goal, NASA scientists have tried this type of thing before with the Viking landers so they know what sorts of tests don't work as expected. The Curiosity rover, outfitted with a huge array of instruments, should be able to perform far more complex measurements and analyses to measure the mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and to search for any potential chemical building blocks for life. Orbiting spacecraft had previously identified certain minerals within the crater that may have formed in a watery environment, so Curiosity will study these minerals further. If water did indeed exist to facilitate this mineral formation, then it may have also allowed microbial life to exist within the environment as well. Within the Gale Crater there also exists a mountain roughly 3 miles high named Aeolis Mons that Curiosity intends to investigate.

Mars has drawn the attention and inspired the imagination of humanity for well over 100 years. Since Percival Lowell's time spent at the telescope observing what he believed to be canals made by an intelligent but dying civilization, mankind has wondered about the existence of life on our red neighbor. While the existence of such canals was later dismissed, observations of changing dark features on the Martian surface and a spectrum that mimicked that of chlorophyll seemed to suggest that Mars may be covered with some form of vegetation that changed with the seasons. These observations led to the development of many great science-fiction thrillers, from "The War of the Worlds", written in 1898 by H.G. Wells and adapted into both a terrifying radio program and two movies, to "Invaders from Mars" and "Mars Attacks", people have wondered about the possibility of

hostile life on this mysterious world. Other speculative movies linking life on Mars to life on Earth include "Mission to Mars" and "Red Planet". And let's not forget "John Carter" and "Total Recall." While these movies vary in quality, they all address the idea of sending humans to Mars or being visited by beings from Mars.

While the Mariner missions revealed to us that Mars appears to be a dead planet, it does retain some characteristics that make it somewhat Earth-like. A wispy thin carbon dioxide atmosphere, canyons, mountains, and polar ice caps all bring to mind thoughts of Earth. However, its vast lifeless deserts and cratered surface more closely resemble the Moon. Mineralogical evidence that liquid water may have at one time existed on Mars have motivated mission after mission to explore its surface and look for fossilized evidence of life. Now that we have landed the most sophisticated instrument lab yet, we may be able to finally answer this question once and for all.

You can keep up with the Curiosity rover's progress and scientific findings via the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's website at http://mars.jpl.nasa.gov/msl/.

Friday, June 29, 2012

July - a great time to use that new telescope!

With the Venus transit behind us now, it seems that the astronomical skies are "calming down" - at least for now. But that doesn't mean there is nothing to hunt down on any given night. The sky is full of potential targets, whether using binoculars or a telescope, so let's take a look at what is coming up in July.

Unfortunately for you naked-eye viewers, there are no meteor showers scheduled for July. The next one isn't until mid-August (the Perseids). However, with the full moon occurring on July 3, this leaves many of the early and mid-month evenings available for reasonably dark-sky constellation viewing. Mars is currently making the transition into the constellation of Virgo right now, gradually drawing closer to Saturn in the sky. At the same time, these two bright planets are beginning to appear lower and lower in the west as the weeks go on, so be sure to spot them before they are gone.

If you got a new set of nice binoculars or a telescope for Christmas and have been anxiously awaiting those warm summer nights to learn how to use it, this would be a great time to get it out. While you may not yet know what exactly to look at - particularly if your telescope isn't motorized - you can still learn the fine art of star-hopping. Find a star map online (free all-sky maps can be found here) or you could download one of any number of astronomy apps if you have a smartphone and you're ready to go. While your binocs or telescope will show more stars than may appear on your star map, you'll gradually get the hang of locating the next star by comparing relative positions and brightnesses. Nothing in astronomy comes easily, but learning is part of the fun. Once you are a master star-hopper, download maps of the Messier objects and push your equipment to the limit. If you are using binoculars for this, you may wish to purchase a tripod and mount for them to hold them steady.

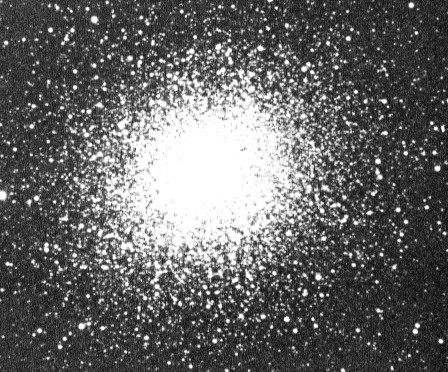

Star clusters are fantastic objects to point your viewing instrument at because they're generally bright enough to see even with small binoculars. The globular cluster M13, for example, is high in the sky all night this month in the constellation of Hercules - hence its unofficial title "The Hercules Cluster." The image below (courtesy of SEDS) will give you an idea of what to expect.

Of course, this is an image taken with a camera so your view through the eyepiece won't be so rich or saturated, but you may find that you prefer the eyepiece view even better! As you examine its stellar population, think about the fact that this cluster is believed to be at least twice as old as our solar system and contains several hundred thousand stars all packed into an area roughly 150 light-years across. Try to count the stars yourself to see how many you can see with your equipment. Imagine what the night sky would look like if you lived on a planet orbiting one of these stars. Then go exploring to see what else you can find!

Happy viewing!

Unfortunately for you naked-eye viewers, there are no meteor showers scheduled for July. The next one isn't until mid-August (the Perseids). However, with the full moon occurring on July 3, this leaves many of the early and mid-month evenings available for reasonably dark-sky constellation viewing. Mars is currently making the transition into the constellation of Virgo right now, gradually drawing closer to Saturn in the sky. At the same time, these two bright planets are beginning to appear lower and lower in the west as the weeks go on, so be sure to spot them before they are gone.

If you got a new set of nice binoculars or a telescope for Christmas and have been anxiously awaiting those warm summer nights to learn how to use it, this would be a great time to get it out. While you may not yet know what exactly to look at - particularly if your telescope isn't motorized - you can still learn the fine art of star-hopping. Find a star map online (free all-sky maps can be found here) or you could download one of any number of astronomy apps if you have a smartphone and you're ready to go. While your binocs or telescope will show more stars than may appear on your star map, you'll gradually get the hang of locating the next star by comparing relative positions and brightnesses. Nothing in astronomy comes easily, but learning is part of the fun. Once you are a master star-hopper, download maps of the Messier objects and push your equipment to the limit. If you are using binoculars for this, you may wish to purchase a tripod and mount for them to hold them steady.

Star clusters are fantastic objects to point your viewing instrument at because they're generally bright enough to see even with small binoculars. The globular cluster M13, for example, is high in the sky all night this month in the constellation of Hercules - hence its unofficial title "The Hercules Cluster." The image below (courtesy of SEDS) will give you an idea of what to expect.

Of course, this is an image taken with a camera so your view through the eyepiece won't be so rich or saturated, but you may find that you prefer the eyepiece view even better! As you examine its stellar population, think about the fact that this cluster is believed to be at least twice as old as our solar system and contains several hundred thousand stars all packed into an area roughly 150 light-years across. Try to count the stars yourself to see how many you can see with your equipment. Imagine what the night sky would look like if you lived on a planet orbiting one of these stars. Then go exploring to see what else you can find!

Happy viewing!

Friday, June 8, 2012

Venus Transit, Conquered

Oneonta weather gave us some challenges when it came time to observe the last Venus transit for 105 years, but it was worth it! This entry is a description of the evening's event as I described it to the folks who write for the College news.

The evening began with a solid cloud deck and rain, but by 6:00 the rain had stopped and the clouds had slightly thinned. By that point, Shawn Grove (a 2012 SUNY Oneonta graduate) and I were joined by 5 or 6 people from the community in the observatory waiting for the weather to clear. The transit technically began at 6:03 p.m. here in Oneonta, and around 6:10 we were suddenly greeted with a thin spot in the clouds where we could see the disk of the Sun. Quickly we pointed the 14-inch telescope at it and were greeted with a view showing Venus approximately halfway through its "entrance" into the solar disk. It looked like a dark dimple in the edge of the Sun. Those who were present were very excited to see this, although it only lasted a few minutes before the clouds thickened up again. From then we waited for over an hour, watching as small gaps in the clouds passed by outside the vicinity of the Sun. More people from the community arrived, and some waited while others left.

Then at about 7:20 p.m. we saw sunlight streaming through another break in the clouds. By this time the Sun had dropped low enough that it was behind trees, so we couldn't see it from the elevated 14-inch dome. However, we did have a smaller 4.5-inch telescope with a solar filter on the ground that we could move. Grabbing it, we raced across the grassy lawn to a point where the Sun was visible. Venus was well into its transit by then so we were blessed with the view that is shown in the image below.

The clouds remained thin enough to see it clearly while the group of roughly 15 people, including several children, each took turns looking through the small scope. A handful of people had gone into the woods to check out the nearby pond and when we called out to them they came sprinting out of the woods. Everyone was able to see it, many people took pictures with camera phones (and me with my digital camera), and by 7:45 p.m. the clouds obscured the Sun again just as it dropped below the tree line for good.

Part of the excitement was that "thrill of the hunt" feeling from waiting and then pursuing with the small telescope in hand. Another part of the excitement came from being able to witness an event that won't occur for another 105 years. However, I think the greatest satisfaction for me was being able to see people from the community come up in the hopes of seeing the transit, be rewarded for their diligence, and walk away feeling like it had been worth the wait. Everyone was thrilled to have been able to see it. Thank you to everyone who came out to see it!

The evening began with a solid cloud deck and rain, but by 6:00 the rain had stopped and the clouds had slightly thinned. By that point, Shawn Grove (a 2012 SUNY Oneonta graduate) and I were joined by 5 or 6 people from the community in the observatory waiting for the weather to clear. The transit technically began at 6:03 p.m. here in Oneonta, and around 6:10 we were suddenly greeted with a thin spot in the clouds where we could see the disk of the Sun. Quickly we pointed the 14-inch telescope at it and were greeted with a view showing Venus approximately halfway through its "entrance" into the solar disk. It looked like a dark dimple in the edge of the Sun. Those who were present were very excited to see this, although it only lasted a few minutes before the clouds thickened up again. From then we waited for over an hour, watching as small gaps in the clouds passed by outside the vicinity of the Sun. More people from the community arrived, and some waited while others left.

Then at about 7:20 p.m. we saw sunlight streaming through another break in the clouds. By this time the Sun had dropped low enough that it was behind trees, so we couldn't see it from the elevated 14-inch dome. However, we did have a smaller 4.5-inch telescope with a solar filter on the ground that we could move. Grabbing it, we raced across the grassy lawn to a point where the Sun was visible. Venus was well into its transit by then so we were blessed with the view that is shown in the image below.

The clouds remained thin enough to see it clearly while the group of roughly 15 people, including several children, each took turns looking through the small scope. A handful of people had gone into the woods to check out the nearby pond and when we called out to them they came sprinting out of the woods. Everyone was able to see it, many people took pictures with camera phones (and me with my digital camera), and by 7:45 p.m. the clouds obscured the Sun again just as it dropped below the tree line for good.

Part of the excitement was that "thrill of the hunt" feeling from waiting and then pursuing with the small telescope in hand. Another part of the excitement came from being able to witness an event that won't occur for another 105 years. However, I think the greatest satisfaction for me was being able to see people from the community come up in the hopes of seeing the transit, be rewarded for their diligence, and walk away feeling like it had been worth the wait. Everyone was thrilled to have been able to see it. Thank you to everyone who came out to see it!

Monday, June 4, 2012

Venus Transit of the Century

With a plethora of websites dedicated to tomorrow's transit of Venus across the face of the Sun, including a page on Wikipedia about it, I don't feel the need to wax eloquent about the upcoming event in too much detail. Numerous sources can be read to learn about the orbits of Venus and Earth, the importance it once had in determining the distance scales of our solar system, and so on. However, since this blog is dedicated to the observer in the Oneonta, NY region, you're probably wondering about when it will be visible.

The most recent transit of Venus occurred in early June of 2004. This transit occurred in the early morning in North America, with viewers in New York seeing it already in progress as the sun rose. This made the event a bit of a challenge to see, since getting up before the sun rises isn't on most people's list of favorite things to do. In Michigan at this time, I would have been an undergraduate at Central Michigan University. Since I was an avid astronomer and astronomy student at the time, if it had been visible then I'm sure I would have gone to see it at our school's telescope. The fact that I don't have any memories of it makes me think it may have been cloudy that day.

For those who don't know me...I have a terrible memory. Case in point: I currently have 13 Post-it notes on my desk at this very moment with reminders for various things! Not to mention the five half-page sized pieces of paper with other various notes jotted on them and an index card of notes as well. But I digress...

The 2012 Venus is visible in North America in the early evening until sunset, making it much more accessible for the average viewer. Expected to begin at approximately 6:00 p.m. in Oneonta, the second planet from the Sun (and our closest planetary neighbor) will continue its sojourn across our star's face until well after the sun has set, giving us only a limited opportunity to watch it for approximately an hour and a half.

The current weather forecast is for clouds and possibly rain. If you're a sucker for "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunities, you may want to take a trip somewhere else to watch it - preferably farther west where you can watch it for a longer time period.

HOWEVER! The Internet now offers the couch-astronomer and those of us in cloudy parts of the planet the chance to watch this event live as seen from somewhere else. You can visit the website for the SLOOH Space Camera or NASA's live webcast from Mauna Kea, Hawaii. I recommend tuning into the webcast shortly before 6:00 p.m. EDT to make sure you see it. If you want it to feel like you're really there watching it through a telescope, get a paper towel tube and hold it up to your computer screen. Who says you need fancy equipment? The Internet is pretty fancy in my opinion!

If you are in the Oneonta area and the weather magically happens to be clear in the late afternoon on June 5, come see us at the SUNY Oneonta observatory at College Camp. We will have a couple telescopes with solar filters for safe viewing set up. Don't look directly at the sun for this event, or permanent eye damage may result. We will have safe equipment for viewing the event. Our viewing of the Sun and the eclipse will be open to the public starting at 5:30 p.m.

If the weather looks bad, hop online and visit one of the websites above. This is what I did for the most recent annular solar eclipse and it wasn't bad. Better than missing it altogether, anyway!

Happy viewing!

The most recent transit of Venus occurred in early June of 2004. This transit occurred in the early morning in North America, with viewers in New York seeing it already in progress as the sun rose. This made the event a bit of a challenge to see, since getting up before the sun rises isn't on most people's list of favorite things to do. In Michigan at this time, I would have been an undergraduate at Central Michigan University. Since I was an avid astronomer and astronomy student at the time, if it had been visible then I'm sure I would have gone to see it at our school's telescope. The fact that I don't have any memories of it makes me think it may have been cloudy that day.

For those who don't know me...I have a terrible memory. Case in point: I currently have 13 Post-it notes on my desk at this very moment with reminders for various things! Not to mention the five half-page sized pieces of paper with other various notes jotted on them and an index card of notes as well. But I digress...

The 2012 Venus is visible in North America in the early evening until sunset, making it much more accessible for the average viewer. Expected to begin at approximately 6:00 p.m. in Oneonta, the second planet from the Sun (and our closest planetary neighbor) will continue its sojourn across our star's face until well after the sun has set, giving us only a limited opportunity to watch it for approximately an hour and a half.

The current weather forecast is for clouds and possibly rain. If you're a sucker for "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunities, you may want to take a trip somewhere else to watch it - preferably farther west where you can watch it for a longer time period.

HOWEVER! The Internet now offers the couch-astronomer and those of us in cloudy parts of the planet the chance to watch this event live as seen from somewhere else. You can visit the website for the SLOOH Space Camera or NASA's live webcast from Mauna Kea, Hawaii. I recommend tuning into the webcast shortly before 6:00 p.m. EDT to make sure you see it. If you want it to feel like you're really there watching it through a telescope, get a paper towel tube and hold it up to your computer screen. Who says you need fancy equipment? The Internet is pretty fancy in my opinion!

If you are in the Oneonta area and the weather magically happens to be clear in the late afternoon on June 5, come see us at the SUNY Oneonta observatory at College Camp. We will have a couple telescopes with solar filters for safe viewing set up. Don't look directly at the sun for this event, or permanent eye damage may result. We will have safe equipment for viewing the event. Our viewing of the Sun and the eclipse will be open to the public starting at 5:30 p.m.

If the weather looks bad, hop online and visit one of the websites above. This is what I did for the most recent annular solar eclipse and it wasn't bad. Better than missing it altogether, anyway!

Happy viewing!

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

How to Buy a Telescope for Yourself

Throughout this blog I have made reference to viewing various celestial objects and events through binoculars or a telescope, and this works fairly well if you already own one or both such instruments. However, suppose you don't own either one - or, suppose you own a pair of binoculars but are itching to buy a telescope. It is perhaps the most common question that novice astronomers and non-astronomers ask experienced amateur and professional astronomers: "I'd like to purchase my first telescope. What telescope should I buy?" Today I will provide you with some instructions and advice that should (hopefully) be of use to you as you begin shopping around. In a future entry I will explain how to purchase a telescope for your child.

Before You Begin

If you are new to the night sky, then I would suggest buying a pair of nice binoculars first. You can drop $100 at Walmart for a cheap telescope that will quickly disappoint, or you can buy a quality pair of binoculars at the same cost that will provide better image quality. Yes, you are losing out on magnification (although don't buy the pitch from the cheap retail telescopes that claim 500X magnification!), but what you are gaining is an easily-transported, well-made optical instrument that will introduce you to the night sky before you get lost using a new telescope.

Here is a common scenario: you enthusiastically run to the store to buy a telescope, spend $150 on one that promises incredible magnification and comes in a box plastered with amazing images of planets, nebulae, and galaxies, then take it home and don't know what to look at. This occurs because the telescope didn't come with a drive motor or computerized paddle - you know you'd like to look at Saturn, but don't even know where Saturn is. You go inside also wishing you knew what season the constellation Orion was visible, pack the telescope in its box, and it subsequently collects dust.

Is the best choice to go buy a nice computerized telescope? Not unless you'd like to spend $500 or more on something that will likely sit in your garage or basement for the foreseeable future. Buying a nice pair of binoculars and a star atlas allows you to fall in love with the night sky. Go outside, lay on a blanket, and use your star atlas to guide you from star to star through a constellation. Binoculars have sufficient magnification (the first number in the specs: for example, "7x50" binoculars have a magnifying power of 7X and an aperture of 50 mm) as to reveal rich open star clusters, the phases of Venus, the Galilean moons of Jupiter, and exquisite lunar features. Star-hopping like this helps to familiarize yourself with the night sky. Using star maps from an atlas or an astronomy magazine, you can become an expert in night-sky viewing. Then go buy a telescope.

Types of Telescopes

There are several different kinds of telescopes that can be differentiated by the optical elements they utilize and the mounts on which they are built.

Choosing a Telescope

When you are ready to purchase your first telescope, there are a number of factors that you should consider. These factors are (in no particular order):

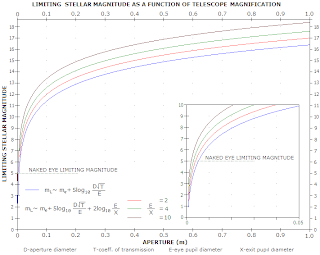

Optical quality: If the quality of the lens or mirrors in your telescope is poor, your viewing experience will be poor as well. Department store telescopes are made with cheap glass lenses that offer more aberration than acclamation. A telescope retailer (either a store or online) will provide better quality options. You want a telescope that uses quality lenses or mirrors! This ties in with aperture size too. In general, bigger is better. However, bigger is also more expensive. You'll need to strike a balance. You can use a diagram like this to determine your optimal aperture size:

"Limiting stellar magnitude" in this diagram simply refers to the faintest object you can see through the telescope. Larger numbers correspond to fainter objects. Between 6-10 inches in aperture diameter typically provides a reasonable performance for its cost. Refractors have smaller apertures than most reflectors, but can provide better images if you pay for it. For reference, planets are bright, galaxies are faint. Planets are easily visible in nearly all telescopes, while galaxies are only visible with larger apertures - typically greater than 10 inches.

Portability: Will you be taking your telescope on trips, or will it always be used outside? Will you be the one using it, or will your child? Portability is an important thing to consider depending on your plans for the telescope. Larger telescopes and sturdier mounts are heavier to move around and sometimes require a bit of dis-assembly to transport. Additionally, if your telescope has a drive motor and/or computer it may require a source of electricity.

Time available for use: How often do you envision the telescope being used? Once a week? Once a month? Only once? If you will use it a lot, you may wish to spend more on one that will provide a lifetime of viewing options - this generally means purchasing a larger telescope with a broad range of eyepieces. If it will be used only on occasion, then don't spend more than $500. If this might be used once or twice before interest in it wanes, don't spend more than $300.

Ease of use: How good are you at learning to use new equipment? Is this for a child or an adult? Simple telescopes may look "too basic" but they are much easier to use than computerized telescopes. They act as "point-and-shoot" telescopes, and all you really need to learn is how to point them using the axis knobs. However, you also need to be familiar with the night sky. Motorized, computerized telescopes make it very easy to find things...provided that you have it plugged in and set up properly and have done a correct alignment using several stars in the sky. Motorized telescopes have thicker user manuals.

The Final Choice

After you have considered all these factors, it comes down to making a choice. Many amateur astronomers will go with a 6- or 8-inch Dobsonian reflector and be very happy with it. Others prefer to buy a nice 3- or 4-inch refractor and get superb views of solar system objects. Motorized SCTs are extremely hard to find under $700 unless you buy one secondhand. All things considered, I prefer to recommend getting as much aperture as you can afford. A great 4-inch refractor is nice, but at the cost of something like that you can get a 12-inch reflecting telescope with a drive motor that will allow you to see many more types of objects than the smaller refractor. Consider the factors I have mentioned above carefully, then talk to a telescope retailer to find one that will best fit your desires.

Resources

Check out some of these manufacturer websites to see your options and their costs:

Before You Begin

If you are new to the night sky, then I would suggest buying a pair of nice binoculars first. You can drop $100 at Walmart for a cheap telescope that will quickly disappoint, or you can buy a quality pair of binoculars at the same cost that will provide better image quality. Yes, you are losing out on magnification (although don't buy the pitch from the cheap retail telescopes that claim 500X magnification!), but what you are gaining is an easily-transported, well-made optical instrument that will introduce you to the night sky before you get lost using a new telescope.

Here is a common scenario: you enthusiastically run to the store to buy a telescope, spend $150 on one that promises incredible magnification and comes in a box plastered with amazing images of planets, nebulae, and galaxies, then take it home and don't know what to look at. This occurs because the telescope didn't come with a drive motor or computerized paddle - you know you'd like to look at Saturn, but don't even know where Saturn is. You go inside also wishing you knew what season the constellation Orion was visible, pack the telescope in its box, and it subsequently collects dust.

Is the best choice to go buy a nice computerized telescope? Not unless you'd like to spend $500 or more on something that will likely sit in your garage or basement for the foreseeable future. Buying a nice pair of binoculars and a star atlas allows you to fall in love with the night sky. Go outside, lay on a blanket, and use your star atlas to guide you from star to star through a constellation. Binoculars have sufficient magnification (the first number in the specs: for example, "7x50" binoculars have a magnifying power of 7X and an aperture of 50 mm) as to reveal rich open star clusters, the phases of Venus, the Galilean moons of Jupiter, and exquisite lunar features. Star-hopping like this helps to familiarize yourself with the night sky. Using star maps from an atlas or an astronomy magazine, you can become an expert in night-sky viewing. Then go buy a telescope.

Types of Telescopes

There are several different kinds of telescopes that can be differentiated by the optical elements they utilize and the mounts on which they are built.

- Refractors: Refracting telescopes are long and narrow tubes with a glass lens on one end and an eyepiece on the other: These telescopes can be on equatorial mounts (shown above) or altitude-azimuth mounts (which are easier for pointing, harder for tracking). Cheap models will have one simple lens at the aperture (the big end), while higher quality models will have a two-piece (achromatic) or three-piece (apochromatic) compound lens. The more lenses, the better the image quality because these additional lenses are correcting for an effect called "chromatic aberration" where different colors are focused at different distances by the glass lens. Of course, the more compound the lens, the higher the cost as well. Many refractors are not motorized, although some of the high-end ones can be.

- Reflectors: Reflecting telescopes utilize mirrors to focus the light rather than an aperture lens: These can be long or short, and most often have an open aperture with a mirror on the lower end. The light is reflected off this mirror to a smaller, flat mirror up near the opening and then directed out the side of the telescope through the eyepiece. Reflectors do not have chromatic aberration and typically offer more bang for your buck as far as aperture size goes. The larger the aperture, the more light is collected - producing a brighter image with better resolution. Equatorial mount reflectors can come in both motorized and non-motorized forms.

- Dobsonians: Dobsonian telescopes are simply reflecting telescopes that sit on the ground in an altitude-azimuth mount: Other than this mount difference, they have the same characteristics as other reflectors while also providing much longer focal lengths - giving you higher magnification capabilities (provided you have the right eyepieces). Dobsonians are almost never motorized, but many do come with a computer paddle that tells you which direction to move the telescope by hand. This is a reasonable compromise between paying less for a non-motorized telescope while also having the advantage of a built-in object library.

- Schmidt-Cassegrains: The final "general" category is the Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescope (SCT) that uses both a lens and mirrors to focus light: These provide great image quality, high magnification potential, and are usually computerized...but they are also expensive.

Choosing a Telescope

When you are ready to purchase your first telescope, there are a number of factors that you should consider. These factors are (in no particular order):

- Budget

- Optical quality / aperture size

- Portability

- Time available for use

- Ease of use

Optical quality: If the quality of the lens or mirrors in your telescope is poor, your viewing experience will be poor as well. Department store telescopes are made with cheap glass lenses that offer more aberration than acclamation. A telescope retailer (either a store or online) will provide better quality options. You want a telescope that uses quality lenses or mirrors! This ties in with aperture size too. In general, bigger is better. However, bigger is also more expensive. You'll need to strike a balance. You can use a diagram like this to determine your optimal aperture size:

"Limiting stellar magnitude" in this diagram simply refers to the faintest object you can see through the telescope. Larger numbers correspond to fainter objects. Between 6-10 inches in aperture diameter typically provides a reasonable performance for its cost. Refractors have smaller apertures than most reflectors, but can provide better images if you pay for it. For reference, planets are bright, galaxies are faint. Planets are easily visible in nearly all telescopes, while galaxies are only visible with larger apertures - typically greater than 10 inches.

Portability: Will you be taking your telescope on trips, or will it always be used outside? Will you be the one using it, or will your child? Portability is an important thing to consider depending on your plans for the telescope. Larger telescopes and sturdier mounts are heavier to move around and sometimes require a bit of dis-assembly to transport. Additionally, if your telescope has a drive motor and/or computer it may require a source of electricity.

Time available for use: How often do you envision the telescope being used? Once a week? Once a month? Only once? If you will use it a lot, you may wish to spend more on one that will provide a lifetime of viewing options - this generally means purchasing a larger telescope with a broad range of eyepieces. If it will be used only on occasion, then don't spend more than $500. If this might be used once or twice before interest in it wanes, don't spend more than $300.

Ease of use: How good are you at learning to use new equipment? Is this for a child or an adult? Simple telescopes may look "too basic" but they are much easier to use than computerized telescopes. They act as "point-and-shoot" telescopes, and all you really need to learn is how to point them using the axis knobs. However, you also need to be familiar with the night sky. Motorized, computerized telescopes make it very easy to find things...provided that you have it plugged in and set up properly and have done a correct alignment using several stars in the sky. Motorized telescopes have thicker user manuals.

The Final Choice

After you have considered all these factors, it comes down to making a choice. Many amateur astronomers will go with a 6- or 8-inch Dobsonian reflector and be very happy with it. Others prefer to buy a nice 3- or 4-inch refractor and get superb views of solar system objects. Motorized SCTs are extremely hard to find under $700 unless you buy one secondhand. All things considered, I prefer to recommend getting as much aperture as you can afford. A great 4-inch refractor is nice, but at the cost of something like that you can get a 12-inch reflecting telescope with a drive motor that will allow you to see many more types of objects than the smaller refractor. Consider the factors I have mentioned above carefully, then talk to a telescope retailer to find one that will best fit your desires.

Resources

Check out some of these manufacturer websites to see your options and their costs:

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

Eclipse Update

After reviewing an interactive and animated web tool called Shadow & Substance, it appears that Oneonta may not get to experience even a partial solar eclipse on May 20 after all. It seems we are just a bit too far east. I had hoped that our altitude might help to override this, but it looks like that may not be the case. At any rate, this will not stop me, and should not stop YOU, from keeping an eye on the Sun as it approaches the horizon. Right at the point of sunset it may be possible to see the slightest piece of the Sun become obscured by the Moon. Try to find a place up in the hills that has a clear view of the western horizon (no trees). If you miss it, then wait until August 2017! There will be a partial solar eclipse visible from Oneonta for sure.

Venus is beginning to set earlier and earlier in the evening now. It has passed its greatest elongation and is not heading down into the glare of the Sun. On June 5th it will transit in front of the Sun, with first contact occurring at about 6:10 p.m. EDT. I will write about this in more detail as the date gets closer. In the meantime, pray for clear skies!

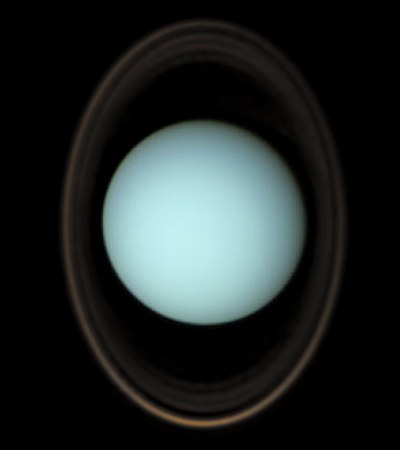

Saturn is continuing to be a stunning sight through most telescopes. With its rings tilted at a 13-degree angle to our light of sight, they are easily spotted. During our most recent public observing night at College Camp, the air was still enough that even the Cassini division was visible in the 16-inch telescope, along with 4 moons (Titan, Tethys, Rhea, and Dione).

What a beautiful vision! Every person who views Saturn through a telescope when the seeing is good remarks how it looks just as if it were a picture held up at the other end of the telescope. Watch Saturn's moons from night to night to see how their positions change.

The semester is coming to a conclusion this week, so I'm busy preparing reports and final grades. Once this has died down, I will be back with another post.

Happy viewing!

Monday, April 30, 2012

Transits, eclipses, and meteors...oh my!

Ever since Venus and Jupiter made a wonderful pass by each other last month, Venus has been dominating the evening sky after sunset. Shining brilliantly in the western sky, Venus has passed its greatest eastern elongation (the point where it is farthest east of the Sun - visible in the evening) and is now on its way back into the sunset glow for the upcoming transit in front of the Sun on June 5th. This will be something nobody alive wants to miss, as the next one won't happen for another 105 years! Until then, we Oneonta residents will hope and pray for clear skies that day. For now, there are still some exciting things to come.

The United States is not often blessed with the opportunity to view a solar eclipse, but this month we will be...in part, anyway. An annular solar eclipse will be visible in the southwestern portion of our country on May 20.

If you live in New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, or California (or will be there on vacation) you will get the chance to see the Moon almost block out the Sun completely. Annular eclipses happen when the Moon lines up perfectly with the Sun in our sky, but is at a point farther away in its orbit around the Earth than average. This results in the Moon having a slightly smaller angular size than the Sun, producing a ring of sunlight around the New Moon instead of being completely blocked out. While not quite as spectacular as seeing a total solar eclipse, annular eclipses are also amazing to watch and certainly, beggars can't be choosers!

Here in Oneonta, we will see a partial solar eclipse beginning around 5:15 p.m. on May 20 and continuing on until sunset. Even though we won't be able to see totality from our location on the Earth, I still plan on viewing this event if our skies are clear. If you plan on viewing the eclipse, be sure to use appropriate eye protection. I will probably use a telescope fitted with a solar filter. More on the eclipse as the date gets closer.

More immediately, we have another meteor shower coming up. On the night/morning of May 4th/5th, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower will be visible. This meteor shower is one of two that derive from the dusty trail of Halley's Comet (the other being the Orionids) and, while not a particularly active meteor shower, can produce 10-20 meteors per hour at its peak. While its radiant won't rise until the early hours before dawn on May 5th, it is usually better to look about 90 degrees away from the radiant anyway to see those dust particles that give us a glancing blow. Viewing after midnight is recommended, but unfortunately this year the Full Moon's overwhelming brightness may hinder attempts to see all but the brightest streaks across the sky. It's still worth a look, however. Additionally, since the maximum technically occurs during the Oneonta afternoon, if you are clouded out on the night of May 4th you can try again on the night of May 5th. Here is a chart showing the radiant of this meteor shower as it is rising in the early hours before dawn in early May:

Happy viewing!

The United States is not often blessed with the opportunity to view a solar eclipse, but this month we will be...in part, anyway. An annular solar eclipse will be visible in the southwestern portion of our country on May 20.

If you live in New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, or California (or will be there on vacation) you will get the chance to see the Moon almost block out the Sun completely. Annular eclipses happen when the Moon lines up perfectly with the Sun in our sky, but is at a point farther away in its orbit around the Earth than average. This results in the Moon having a slightly smaller angular size than the Sun, producing a ring of sunlight around the New Moon instead of being completely blocked out. While not quite as spectacular as seeing a total solar eclipse, annular eclipses are also amazing to watch and certainly, beggars can't be choosers!

Here in Oneonta, we will see a partial solar eclipse beginning around 5:15 p.m. on May 20 and continuing on until sunset. Even though we won't be able to see totality from our location on the Earth, I still plan on viewing this event if our skies are clear. If you plan on viewing the eclipse, be sure to use appropriate eye protection. I will probably use a telescope fitted with a solar filter. More on the eclipse as the date gets closer.

More immediately, we have another meteor shower coming up. On the night/morning of May 4th/5th, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower will be visible. This meteor shower is one of two that derive from the dusty trail of Halley's Comet (the other being the Orionids) and, while not a particularly active meteor shower, can produce 10-20 meteors per hour at its peak. While its radiant won't rise until the early hours before dawn on May 5th, it is usually better to look about 90 degrees away from the radiant anyway to see those dust particles that give us a glancing blow. Viewing after midnight is recommended, but unfortunately this year the Full Moon's overwhelming brightness may hinder attempts to see all but the brightest streaks across the sky. It's still worth a look, however. Additionally, since the maximum technically occurs during the Oneonta afternoon, if you are clouded out on the night of May 4th you can try again on the night of May 5th. Here is a chart showing the radiant of this meteor shower as it is rising in the early hours before dawn in early May:

Happy viewing!

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Don't miss the Lyrid meteor shower

The coming of spring also marks the second significant meteor shower of the year - the Lyrids. Radiating from the constellation of Lyra, this moderately active meteor shower peaks on the evening of April 21st into the morning of the 22nd.

While the Moon has often been an unwelcome visitor during major meteor showers recently, this isn't the case this time. New Moon occurs on the 21st this month, meaning the Moon will set with the Sun. This leaves an entire moonless night of meteor viewing - although the activity will be limited until after midnight. Just as the front windshield of your car collects more rain droplets as you drive than does the rear windshield, once our local part of the Earth has rotated past midnight it becomes the leading face as the Earth moves forward in its orbit around the Sun.

This year's Lyrid meteor shower will likely produce around 20 meteors per hour, although there have been rare instances when the shower produces an outburst of over 50 per hour.

Meteor shower viewing can sometimes produce spectacular bursts of light that you'll remember for years to come. Other times, different causes can produce memorable stories. Several years ago as a graduate student, I headed out for a night of meteor viewing. Grabbing a cup of coffee from a 7-Eleven, I found a dirt road in the middle of farm land and pulled over. I then clambered onto the roof of my car, spread out a blanket, and laid down to watch the sky. Around 3 a.m., a truck slowly drove by my car, checking to see what I was up to. Because it had its headlights on, I closed my eyes to avoid losing my dark adapted vision. About 10 minutes later, a police car pulled up - apparently called by those people in the truck. After a brief chat with the officer and an explanation about the meteor shower happening over our heads, he went on his way - probably shaking his head at the silly young man laying on his car in the middle of the night in a corn field. That's a story I will never forget!

The night air this month will most likely be cold, so make sure you bundle up tight when you head outside. With any luck, there will be no snow on the ground so if you can find a dark location outside of town then bring a blanket and something hot to drink and set up camp to see what this year's Lyrid meteor shower has in store for us.

Happy viewing!